Announcements

campaign

UKRAINE'S RAVAGED

Two years on from the devastating floods in the wake of the Kakhovka Dam destruction, the landscape is returning to its natural state. But climate change and plans for a new dam are threatening the new ecosystem.

campaign

MALI'S JUNTA TIGHTENS

When General Assimi Goita seized power in 2020, many hoped it would bring positive change to Mali, a country grappling with jihadist attacks and an economic crisis. What has actually happened in the past five years?

campaign

ISRAEL'S CONDUCT IN GAZA

The German chancellery insists that the ruling coalition is united in its stance on Israel's actions in Gaza, despite differing views. A split appeared after Germany refused to add its name to a 28-country declaration.

campaign

INDIA'S MAOIST CRACKDOWN

India has vowed to crush the long-running Maoist-inspired Naxal insurgency by March 2026. In the jungles of Chhattisgarh, villagers are mourning those killed in the crossfire.

campaign

ANCESTRAL LANDS

Tamil farmers say the Sri Lankan and Indian governments' plans for a solar power plant in eastern Sri Lanka will use land that was seized during the country's civil war. What is being done to compensate them?

campaign

UKRAINIAN REFUGEE

German politicians are debating whether to slash financial assistance for Ukrainian refugees. How does the country stack up against its EU neighbors when it comes to generosity in helping those fleeing war?

campaign

EARTHQUAKE

Over a dozen buildings collapsed as a result of the tremor, which was felt as far as Istanbul.

campaign

SUFFERING IN GAZA

An international coalition of foreign ministers has condemned the humanitarian situation in the Gaza Strip, calling for Israel to allow vital aid into the besieged enclave.

campaign

HEAT WARNINGS

Temperatures across Germany are soaring, with forecasts reaching up to 37 degrees Celsius in many regions. Also, Friedrich Merz marks his 100th day as chancellor.

campaign

FALL OF ASSAD

Despite German government encouragement, a relatively small number of Syrians have decided to return to their home country.

campaign

CLIMBDOWN

At first glance, Bayern Munich's decision to end its commercial deal with Rwanda appears a rare moment of football morality. But dig a little deeper and the club's motivations seem not so straightforward.

campaign

FLOODING KILLS

Floods triggered by cloudbursts and monsoon rains have killed at least 176 people with many more still missing, authorities in Pakistan and India have said. A helicopter aiding the relief effort also crashed.

campaign

KIRUNA CHURCH

What has wheels and crawls along at half a kilometer an hour? A church in Sweden, of course! A convoy of remote-controlled flatbed trailers is transporting a 113-year-old church to the new city center of Kiruna.

campaign

TRAFFIC DEATHS

The Finnish capital Helsinki went a whole year without a traffic fatality. Smart, data-driven city planning helped.

campaign

FLOODS IN BELGIUM

From Antwerp to Mechelen, restored wetlands act like giant sponges — soaking up stormwater and easing drought. Here's how the plan works, how residents got on board and what's still missing.

campaign

MILD WEATHER

The apple harvest in Germany is expected to be above average in 2025, according to data presented Monday by Germany's statistical office citing harvest estimates as of July.

campaign

GERMANY'S MERZ

The German chancellor said there would be face-to-face talks involving the presidents of Russia and Ukraine. That's after US President Donald Trump made a phone call to Putin as he met with European leaders.

campaign

PUTIN TALKS

After meeting with President Trump, Ukraine's Volodymyr Zelenskyy indicated he was ready to talk with Russian President Vladimir Putin. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz emphasized the need for thorough preparations.

campaign

FAMINE

More than half a million people in Gaza City and parts of the south and central areas of the territory face "starvation, destitution and death," the body responsible for monitoring world hunger has found..

campaign

ECONOMY SHRINKS

Europe's largest economy has shrunk, with industrial production and construction weaker than first thought. Meanwhile, Berlin is being urged to recognize a Palestinian state.

campaign

AID TRUCKS

The first aid trucks have arrived in the Palestinian territory to help ease a worsening humanitarian crisis. Israel has announced a pause in the fighting in some areas to help food distribution.

campaign

SOUND OF FALLING

The Cannes Jury Prize-winning drama by Mascha Schilinski will represent Germany in the best international feature film category.

campaign

TRUMP'S WATCH

Donald Trump's tariffs on BRICS nations outstrip those on the rest of the world. As India, China and Russia prepare for a key summit in Tianjin, has the president forged a tighter alliance among his biggest rivals?

campaign

RUSSIA AND EUROPE

In a show of solidarity, the EU granted both Ukraine and Moldova candidate country status in June 2022. Several European countries, above all Germany, provide Moldova with military support.

campaign

INDUS WATER ROW

The rivers of Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab, which connect India and Pakistan, have for months been the focal point of a slow-moving but embittered dispute between the two rivals.

campaign

TRUMP'S 50% TARIFFS

The deadline for new US tariffs on India has passed early Wednesday, doubling the total levies on goods from the South Asian economic giant to 50%.

campaign

24-HOUR WATCH

Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes asked police to conduct "full-time surveillance" of the 70-year-old, declaring the far-right populist to be a "flight risk."

campaign

AFRICAN NATIONS

How far has francophone Africa come in 65 years? Many African nations celebrate their 65th anniversaries in 2025: Nigeria, Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo all became independent in 1960. France alone granted self-determination to 14 colonies.

campaign

POLISH PRESIDENT

Poland's new president, Karol Nawrocki, announced that he intended to veto the Ukraine Aid Law

campaign

US SENATORS

The visit runs parallel to US President Donald Trump's contentious trade talks with China, which claims Taiwan as its own territory under the "One China" policy.

campaign

ALARM

German authorities have said they investigated more human trafficking and exploitation cases in 2024 than in any year since 2000. Weak online safeguards are a major driver with many minors among the victims.

campaign

CAMBODIA CALL

Paetongtarn Shinawatra was suspended in July following a leaked call with Cambodia's Hun Sen. Friday's verdict by Thailand's top court is a major setback for the powerful Shinawatra political dynasty.

campaign

FUELING

Kyiv's latest strikes on Russian energy infrastructure have angered Hungary, which still relies heavily on Russian oil. Viktor Orban's government has retaliated using diplomatic means.

campaign

PM PAETONGTARN

A Thai court has ordered Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra to step down amid a scandal surrounding her phone call with Cambodia's Hun Sen. The ruling comes as a blow to her Pheu Thai party and her powerful family.

campaign

RUSSIAN ATTACK

Ursula Von der Leyen urged Putin "to come to the negotiating table" after a Russian attack hit an EU office in Kyiv. Ukraine said at least 21 people were killed in overnight Russian strikes.

campaign

VILLAGE LIFE

Thomas Müller seems to be settling in well at the first club he has known apart from Bayern Munich. For a one-club man until a few weeks ago, he also seems to be truly embracing a new city and culture.

campaign

ARMS PLANT

Defense contractor Rheinmetall has opened a new arms-and-explosives plant in Germany. DW spoke with Defense Minister Boris Pistorius about Ukraine's military capabilities and the future of the German military.

campaign

TIGHTENS SECURITY

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto has revoked some of the perks for lawmakers that sparked violent public protests. In response to the crisis, he canceled his attendance at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in China.

campaign

TERRORISM

President Prabowo Subianto has addressed the ongoing protests against economic inequality in Indonesia and appeared to offer major concessions. The protests intensified after police killed a young delivery driver.

campaign

'BULLYING

China's president urged leaders at the summit to reject the "Cold War mentality," in an apparent reference to US policies. Meanwhile, Russia's Vladimir Putin has used the forum to defend his war in Ukraine. DW has more.

campaign

HOUTHI FUNERAL

The new acting leadership of Yemen's Houthi rebels has promised revenge for last week's Israeli strikes. Meanwhile, global media outlets have protested against the deaths of journalists in Gaza. DW has more.

campaign

YOUNG NIGERIANS

Islamist extremists groups like Boko Haram are recruiting new members with the lure of provisions as food shortages hit northern Nigeria. Aid to the region has dwindled after the United States cut its international humanitarian funding.

campaign

PAKISTAN'S PUNJAB

Pakistan's eastern Punjab province is facing one of the worst flood emergencies in recent history. Authorities say raging waters have affected the lives of more than 2 million people.

campaign

BANISHED SMARTPHONES

Greystones, Ireland, pledged to withhold smartphones from children under 12. What does the community think two year on?

campaign

ISRAEL BRACES

Protesters in Israel have begun a "day of disruption" led by relatives of hostages and opponents of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's plans to escalate the offensive in Gaza.

campaign

BALANCING

. In our street debate, we hit the streets of Lagos and ask young people, “Does money make a man?” And then we then highlight the work of a female cinematographer who is pushing the boundaries of what women can achieve.

campaign

VOLUNTEERS

Following arrival in Germany, what’s next? Three people help migrants to build a new life. They advise and translate. They create prospects and encourage people. They live for their commitment - and get a lot back.

campaign

PARLIAMENT

Thailand's acting government is seeking to dissolve the parliament after a rival candidate gained the support of a power-brokering bloc. The dissolution of the parliament would need the Thai king's approval.

campaign

KREMLIN CRITICIZES

German Chancellor Merz described the Russian leader as "the most serious war criminal of our time." Meanwhile, Putin thanked North Korea's Kim Jong Un for his support in the fight against Ukraine.

campaign

FGM

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) left deep scars among Uganda's Sabiny women. But today, they are leading a powerful movement to end the practice — determined to raise a generation of girls who will never have to endure the same pain.

campaign

ACUTE HUNGER

In Nigeria, the number of people facing acute hunger has reached a record of nearly 31 million, the UN says. Northeastern Nigeria has been particularly hard hit. Escalating violence by various militant groups and cuts in global aid have exacerbated the hunger crisis.

campaign

CLIMATE COURSE

Germany's new environment minister faces internal challenges in taking forward both domestic and international climate policy. But he is determined that it will not alter the country's carbon neutral direction.

campaign

LEGITIMATE TARGETS

The Kremlin views any Western military deployment in Ukraine as a threat and would regard them as "legitimate targets for destruction." Meanwhile, Ukraine has struck a Russian oil refinery overnight.

campaign

GLOBAL AFFAIRS

Germany's chancellor is concerned Europe is not playing the role it should on the world stage. Meanwhile, police detained a suspect accused of stabbing a teacher at a vocational school in Essen.

campaign

GAZA

Frustration with Germany is growing in Europe as a "growing majority" of EU member states want to sanction Israel over its conduct in Gaza. What would it take for the German government to change course?

campaign

TEACHER INJURED

A suspect was shot at before being taken into custody in a large police operation after a teacher was stabbed in the stomach in western Germany.

campaign

MAORI QUEEN

The queen of New Zealand's Maori tribe gave her first national address. She ended a year of public silence following her father's death..

campaign

YOUNG FACE

Lithuania’s Martynas Levickis brings the accordion to a whole new level.

campaign

WIN

After their football World Cup qualifying campaign got off to a disastrous start, Germany responded with a win over Northern Ireland.

campaign

EU ASYLUM

The significant decline in overall asylum claims was due to the massive reduction in applications from Syrians seeking protection.

campaign

6 KILLED

Emergency services confirmed the deaths of six people in a shooting at Ramot Junction. It is not yet clear who is responsible for the attack.

campaign

CDU PUSH

Conservative politicians are pushing for more efforts to encourage refugees from Syria to return home. Meanwhile, the Bundestag has launched an inquiry into the country's COVID-19 response.

campaign

JOB

Annalena Baerbock, former Green Party politician and foreign minister, has moved to New York to start her new job on September 9. Not everyone is happy that she will be presiding over the UN's main policy-making organ.

campaign

LABOUR PARTY

The rising cost of living and tumultous geopolitics were the key issues during the campaign. The ruling center-left Labour Party is expected to edge out more conservative parties in the parliamentary election.

campaign

ISHIBA'S RESIGNATION

As rival candidates prepare to stake their claims, will Japan move to the right, or will the moderates once more be given the reins of government?

campaign

FACING DEFEAT

France risks losing its third prime minister in 12 months with the government expected to lose a confidence vote over planned austerity measures. The instability is set to ramp up pressure on President Emmanuel Macron.

campaign

AUTOCRAT

Burkina Faso's military ruler is hailed on social media as a pan-African revolutionary. Yet at home, he suppresses civil liberties, criminalizes homosexuality and silences dissent.

campaign

EU SUSPENDS

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen says the bloc is suspending payments to Israel and proposing sanctions on "extremist" Israeli ministers. China and Russia have condemned Israel's strike in Qatar.

campaign

NEPAL'S ARMY

The Nepali army has announced an indefinite curfew in Kathmandu as it tries to bring normalcy to the city after violent protests against corruption.

campaign

NATO

NATO member Poland said it scrambled defenses in response to 19 airspace breaches. Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk said many of the drones came from Belarus. DW has the latest.

campaign

KFW BANK

The government's development bank is accused of backing harmful projects in emerging markets. Instead of uplifting communities, a new report says investments fail to protect human rights and silence those who speak out.

campaign

NBA SUPERSTAR

World champions Germany will face Slovenia's Luka Doncic in the quarterfinals. The Lakers star is not unbeatable though.

campaign

$1.1 BILLION

The undersea drones can attack from shore and from surface warships, with Australia referring to them as having "the highest tech capability in the world."

campaign

ILLEGAL TRASH

A now bust German company illegally dumped hundreds of tons of hazardous waste in Czech municipalities. Authorities of both countries have been left to clean up the mess.

campaign

LAWMAKERS

After Russian drones were shot down over Poland this week, there are renewed calls to boost Germany's air defense. Meanwhile, Bayer Leverkusen are looking to reboot their Bundesliga season under a new coach.

campaign

CONDUCTOR

The German government has reacted angrily after a Belgian festival canceled a performance by the Munich Philharmonic. Festival organizers cited concerns over its Israeli conductor's political attitude.

campaign

DEATH TOLL

Police say the death toll during violent protests has risen to at least 51 people as the Himalayan nation seeks an interim leader.

campaign

JOINT DRILLS

The show of force by Russia and its key ally comes amid tensions over Russian drones breaching the airspace of NATO member Poland.

campaign

NETANYAHU VOWS

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was speaking during a signing ceremony for a controversial settlement that would effectively cut the occupied West Bank off from East Jerusalem.

campaign

BLAME

The former tennis superstar has written a book about his time in prison in Berlin. Boris Becker uses "Inside" to write about his time behind bars, portraying himself as both a fighter and a victim.

campaign

POWDER KEG

Officially, Transnistria is part of the Republic of Moldova. But in practice, it is a state within a state. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the region seceded in a bloody civil war.

campaign

NEPAL

After deadly youth-led protests, Sushila Karki has become Nepal's first female interim prime minister. DW examines what her anti-corruption legacy means for the country's future.

campaign

GREENS FALL

The conservative CDU remains the strongest party after local elections in North Rhine-Westphalia. However, the far-right Alternative for Germany tripled its 2020 results. The Greens have emerged as the clear losers.

campaign

FRESH PROTESTS

Jina Mahsa Amini's death in police custody in 2022 sparked the "Woman, Life, Freedom" movement in Iran. Three years later, the list of grievances has grown, making the clerical regime more insecure, activists say.

campaign

UKRAINE

Kyiv's defense intelligence said operatives attacked a $40 million Buk-M3 anti-aircraft missile system. Meanwhile, Moscow is calling a drone intrusion in Romania a provocation from Ukraine. DW has more.

campaign

ISRAEL

The EU proposed curbing trade with Israel and placing sanctions on Israeli far-right ministers. Israel opened an exit route out of Gaza City for 48 hours after launching a ground offensive. DW rounds up the latest.

campaign

OFFENSIVE

Israeli forces have labeled Gaza City a "dangerous combat zone." A UN commission's probe has concluded that Israel is committing genocide in the Palestinian enclave, a finding Israel has rejected.

campaign

PUTIN

Russia's violation of Polish and Romanian airspace last week was part of President Vladimir Putin's long-running trend of boundary-testing and sabotage, according to German Chancellor Friedrich Merz.

campaign

GAZA

The EU proposed curbing trade with Israel and placing sanctions on Israeli far-right ministers. Israel opened an exit route out of Gaza City for 48 hours after launching a ground offensive. DW rounds up the latest.

campaign

UNIVERSITIES

DW's Berlin Fresh and The Washington Post Universe's TikTok teams collaborate to explore the perks of living in Berlin and Germany.

campaign

NIGERIA

More than 330 websites have been linked to a phishing operation that stole over 5,000 Micorsoft user credentials.

campaign

INTERSEX PEOPLE

One in six intersex people was physically assaulted in the year 2022, an EU agency report said. Intersex people are the only LGBTIQ group that has not experienced a drop in discrimination since an earlier survey in 2019.

campaign

COUNTRIES

The Eurovision Song Contest is supposed to be apolitical. But Israel is now at the center of calls for boycott and protests, due to the ongoing war in the Gaza Strip.

campaign

NEW CJ

President John Mahama has nominated Supreme Court Judge Justice Paul Baffoe-Bonnie as Ghana’s new Chief Justice.

campaign

DEPORTEES

An Accra High Court has struck out a human rights case filed by eleven West African nationals against the government after it emerged that the applicants had already been deported to their home countries.

campaign

UTAG-UCC

The University Teachers Association of Ghana (UTAG), University of Cape Coast (UCC) chapter, has given the Ghana Tertiary Education Commission (GTEC) 48 hours to reverse its sanctions against the university.

campaign

NPP

New Patriotic Party (NPP) flagbearer hopeful, Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia, is set to appear before the party’s vetting committee today, September 23, as part of the processes leading up to the 2026 presidential primary.

campaign

FREE SPEECH

Former Minister of Health Dr Bernard Okoe Boye has justified the New Patriotic Party (NPP) youth wing’s protest taking place in Accra today, Tuesday, September 23, arguing that the most fundamental feature of Ghana’s democracy, freedom of speech, is under serious threat.

campaign

GIRLS’ CAMP

There are heightened calls for more investments into empowering women and girls in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education as Women in STEM (WiSTEMGh) Ghana bemoans the lack of adequate funding for sustaining opportunities to rope in more females into the field.

campaign

GOLDSTARS

Former Black Stars assistant coach Maxwell Konadu is on the verge of being named the new head coach of Bibiani GoldStars following the departure of Frimpong Manso.

campaign

CURFEW

Four people died following clashes between protesters and police. Demands for political rights in Ladakh have intensified, with some leaders demanding full statehood for the largely Buddhist and Muslim region.

campaign

CAMPAIGN

Former President Nicolas Sarkozy was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison on some charges in a case tied to the late Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi.

campaign

'HYBRID ATTACK

Drones recently spotted over several Danish airports including Aalborg were part of a hybrid attack that Danish Defense Minister Troels Lund Poulsen has said was likely orchestrated by a professional actor.

campaign

DEATH

The weakened storm has moved toward Vietnam, with authorities bracing for landfall. The storm has killed at least 25 people and displaced millions.

campaign

EARTHQUAKE

The US Geological Survey reported the magnitude of the quake, which was located at a depth of 14 kilometers. No casualties have been reported.

campaign

SIGHTINGS

Police are investigating the appearance of drones over the airspace in Aalborg, a city in the north of Denmark. It comes on the heels of the temporary closure of Copenhagen Airport over a similar drone sighting.

campaign

LADAKH REGION

Violent clashes between police and protesters left at least four people dead in Ladakh, a Buddhist-Muslim enclave in the Himalayas. Demonstrators want statehood, job quotas and better representation for tribal areas.

campaign

ISRAEL'S EILAT

The Israeli southern city of Eilat has been hit by a drone fired by the Houthis in Yemen, according to Israeli medics.

campaign

ROLLER-COASTER

One of Germany's top tourist draws has come to a close. The 2025 Oktoberfest saw much revelry — and a few more or less serious hitches. Overall, people drank less, created less trash but lost more stuff than last year.

campaign

GERMAN FIRE

Several calls by residents worried about potential gas leakage caused the fire brigade to investigate before finding the smelly cause: a fruit sold at an Asian supermarket.

campaign

PISTORIUS CALLS

German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius says progress is being made in drone defense. The Oktoberfest is set to close after a not altogether smooth run.

campaign

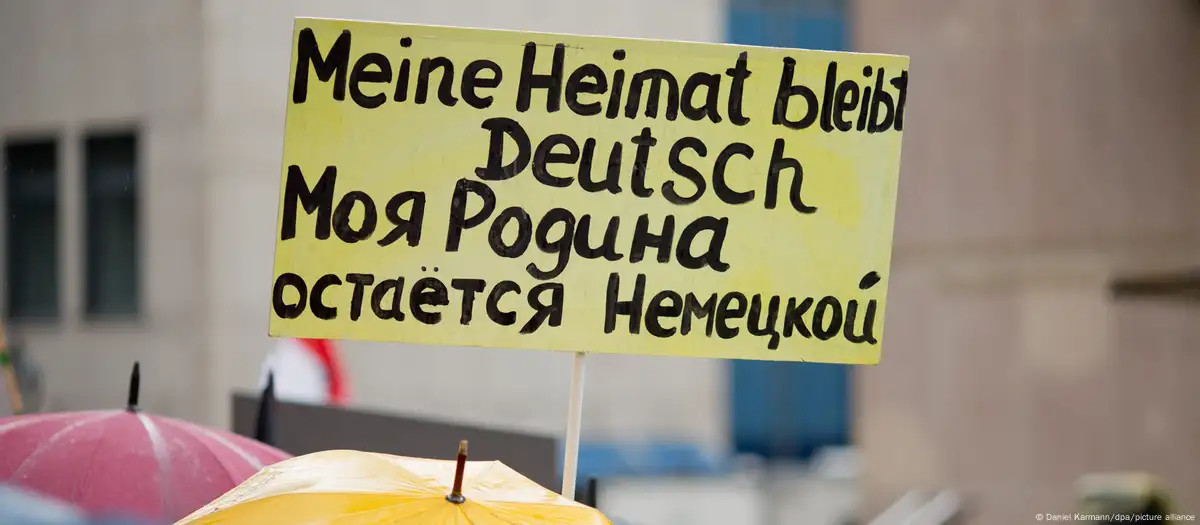

RUSSIA GERMANS

Ethnic Germans who were born in Russia and their descendants are among the most fervent supporters of the far-right Alternative for Germany party. What makes the anti-immigrant AfD appeal to them?

campaign

REUNIFICATION

There is still a wide gap between the former East and West Germany, even amongst young people who have only ever lived in a unified country. The new commissioner for eastern Germany attempts to explain why.

campaign

35

Once a place for alternative lifestyles, now a monument surrounded by offices and luxury apartments: Few other places in Berlin symbolize change as much as the East Side Gallery.

campaign

OBSTACLES

Two years into the war in Gaza between Hamas and Israel, filmmakers who examine the conflict in their works have struggled to find distribution. The Israeli government has also worked to silence critical voices.

campaign

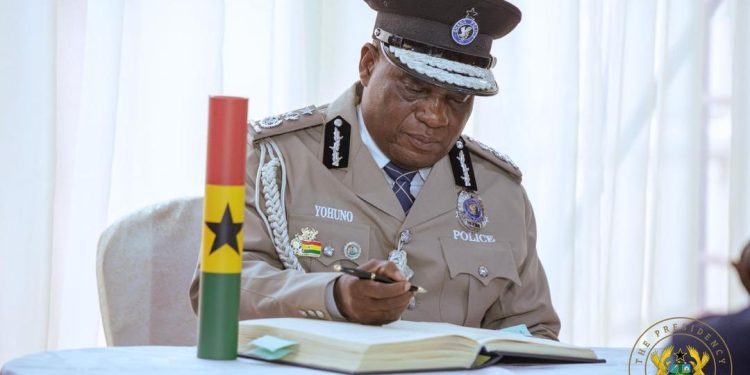

IGP

The Motorcycle Couriers Union of Ghana (MCUG) has petitioned the Inspector General of Police (IGP), Christian Tetteh Yohuno, raising concerns about what they describe as restrictive police operations targeting motorcyclists, particularly couriers, in various parts of the country.

campaign

TRANSPORT FARES

The Ghana Private Road Transport Union (GPRTU) has announced plans to increase transport fares due to persistent instability in fuel prices.Ghana travel guide

campaign

FUTURE

The Global Foundation, Building from Experience From boardrooms in London to investment forums across Europe, Samuel Thompson Acheampong has built a reputation for integrity, innovation, and strategic foresight

campaign

FAILED

Member of Parliament for Effutu and Minority Leader, Alexander Afenyo-Markin, has expressed concern over what he describes as the politicisation of the fight against illegal gold mining, commonly known as galamsey.

campaign

SUSPICIONS

Germany's competition watchdog has announced an investigation of Chinese discount online retail site temu.com, suspecting it of influencing retailers' prices. The site is the fastest-growing of its kind in the world.

campaign

ISRAELI TROOPS

The withdrawal of Israeli troops is part of a deal that also calls for the release of several hundred Palestinian prisoners in exchange for the remaining 48 hostages in Gaza. Follow DW for more.

campaign

RAID HOMES

Investigators have searched the homes and offices of 17 Frankfurt police officers accused of assault and obstruction of justice. Meanwhile, two far-right AfD lawmakers have lost parliamentary immunity. DW has the latest.

campaign

ATHLETES

Mental health has not always been a top consideration in German sport. But on World Mental Health Day, there are signs of change.

campaign

HAMAS

Negotiators for Israel and Hamas have agreed to pause fighting in Gaza to release the remaining hostages in exchange for Palestinian prisoners, adopting parts of a plan backed by US President Trump. Follow DW for more.

campaign

UN OFFICIAL

With minorities excluded from elections, sectarian violence and change slow to come, a UN envoy has warned of a "Libyan scenario" for Syria. Could the country find itself divided among regional governments?

campaign

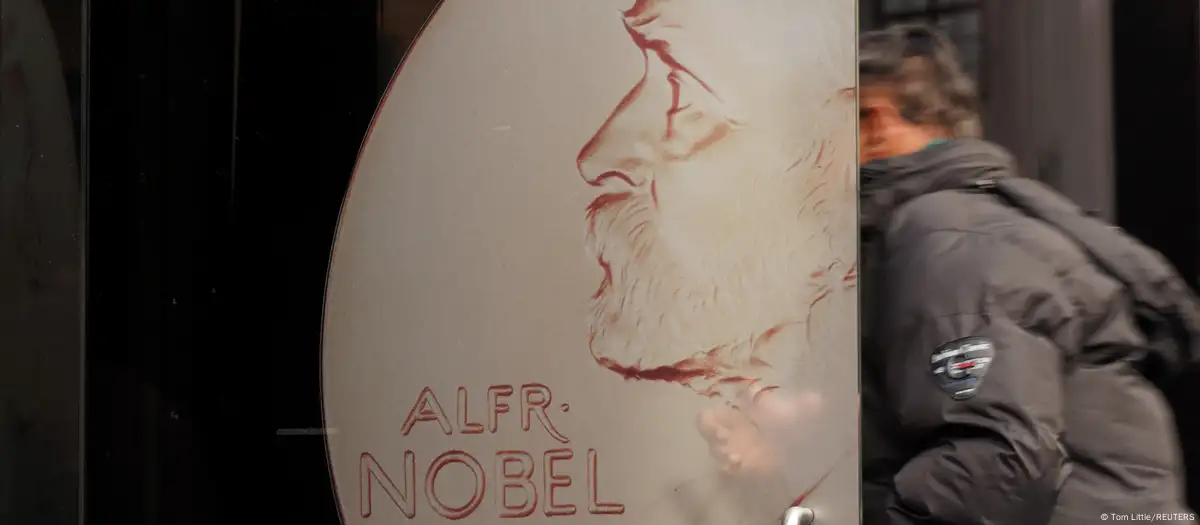

PEACE PRIZE

The Nobel Peace Prize for 2025 has gone to Maria Corina Machado. The committee lauded "her tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela." Follow DW for more.

campaign

MASSIVE ATTACK

Ukraine's air force said the capital had come under a large scale aerial drone and missile bombardment. The country's energy minister said Russia was targeting energy sites. DW has more.

campaign

GAZA SUMMIT

US President Trump has arrived in Egypt for a summit on Gaza, after Hamas freed all remaining living hostages.

campaign

HAMAS THREATS

The leaders of Germany's main intelligence services cautioned the government not to get complacent about Moscow and foreign extremists. Meanwhile, a major apartment fire injured dozens in Berlin.

campaign

MASS PROTESTS

Andry Rajoelina has left Madagascar after losing support in the armed forces and following weeks of youth-led protests. He reportedly left Sunday on a French military plane.

campaign

TRUMP

During a bilateral meeting in Egypt, President Trump said that the second phase of peace negotiations between Hamas and Israel was already underway.

campaign

ZELENSKYY

President Zelenskyy has said he will discuss air-defense and long-range missile capability with President Trump on Friday. This comes amid EU warnings over Moscow's NATO and EU airspace encroachments.

campaign

PALESTINIANS IN GAZA

As people in the Gaza Strip return home after a fragile ceasefire, many find only rubble and loss. With homes destroyed and futures uncertain, the scars of war run deep — and the hope for peace remains fragile.

campaign

CAMEROON

With longtime President Paul Biya facing a divided opposition, more than 8 million Cameroonians voted. Though there was peace at the polls, critics question the fairness and transparency of the electoral process.

campaign

GROWTH

The award went to three researchers from the United States, Canada and France for explaining how technological progress leads to prosperity.

campaign

DRONE DEFENSE

NATO defense ministers are meeting in Brussels after Russian drones and aircraft violated member states' airspace. Meanwhile, the WHO says one of its teams came under attack in Ukraine.

campaign

GAZA AID

The Rafah crossing into Gaza is set to open for aid deliveries after Israel said Hamas had returned the remains of more hostages. Earlier reports said Israel would limit deliveries until more bodies were returned.

campaign

ACTIVE PENSIONER

Germany's Cabinet is looking to allow pensioners to work part-time tax-free after the age of 70. Meanwhile, the coalition is in choppy waters on its military service plans.

campaign

AFGHAN BORDER

Tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan have led to more fighting at the border, with several civilians reported to have been killed.

campaign

2 YEARS PRISON

Austrian real estate developer Rene Benko was found guilty on one count of bankruptcy fraud as he tried to hide cash from duped investors. It was the first of some 14 cases pending against the disgraced developer.

campaign

CEASEFIRE

A new body comprised of Congolese, M23 and regional representatives will be formed to monitor a potential permanent ceasefire. Qatar, the US and the African Union will act as observers.

campaign

NORD STREAM

A court in Rome is hearing an appeal against extradition by a 49-year-old Ukrainian accused of masterminding 2022 Baltic Sea blasts. Germany is seeking to try him for explosive attacks and anti-constitutional sabotage.

campaign

MOSCOW

Syria's president is visiting Russia seeking to reset ties after the fall of long-time ruler Bashar al-Assad. Moscow had been the main ally of the dictator whose regime was toppled by Ahmed al-Sharaa's alliance.

campaign

SCAM CENTERS

Seoul has said 1,000 South Koreans are working at online scam compounds that target victims globally. Some 200,000 forced laborers are thought to be busy stealing billions, from prison-like sites in Cambodia and Myanmar.

campaign

US SHUTDOWN

Local employees at US military bases in Germany are to receive pay from Berlin as a US government shutdown continues. Chancellor Merz has doubled down on his "cityscape" remark about urban migration.

campaign

SANCTIONS PACKAGE

The European Union kicked off its leaders' summit in Brussels by announcing a 19th sanctions package against Russia, which was gratefully acknowledged by Ukraine's Volodymyr Zelenskyy, also in attendance.

campaign

SOLDIER

A police officer mistakenly shot at troops taking part in a large-scale Bundeswehr training exercise in the southern German city of Erding, injuring a soldier.

campaign

GAZA

As the EU held its first-ever bilateral summit with Egypt, activists said the bloc was rewarding an authoritarian government. But experts told DW the EU needs Egypt if it wants to help in Gaza and curb migration at home.

campaign

MIGRANT SMUGGLERS

The UK was hosting a summit of Western Balkan nations, with Prime Minister Keir Starmer having announced measures to curb illegal migration, a top political concern for voters in the country.

campaign

BERLIN

Local employees at US military bases in Germany are to receive pay from Berlin as a US government shutdown continues. Chancellor Merz has doubled down on his "cityscape" remark about urban migration.

campaign

TANZANIANS

As Tanzania's October 29 general election approaches, many voters are calling for leaders who will address everyday challenges — from health care to job creation and education reforms.

campaign

RECRUITS

The reputation of the French Foreign Legion is both legendary and notorious. Every day, men from all over the world come to the legion's barracks in Aubagne. Often, they're looking for a second chance in life.

campaign

DEADLY LADAKH

After years of unfulfilled promises and rising anger, violent protests erupted in Ladakh, a remote region in the Himalayas. Locals say they feel abandoned, while New Delhi faces growing mistrust.

campaign

WEST BANK

The US president said he had given his word to Arab leaders that the annexation will not take place. Vice President JD Vance said the Israeli parliament's vote on West Bank annexation was "an insult."

campaign

NEXPERIA CHIP

European carmakers are reliant on China. A dispute over Dutch chipmaker Nexperia has delivered fresh evidence of the industry's struggles to build resilient supply and value chains.

campaign

PARLIAMENT

The shooting, which President Aleksandar Vucic called an act of terrorism, comes after nearly a year of anti-government protests. The perpetrator called pro-government tents outside parliament an "occupation."

campaign

ELECTION

As Cote d'Ivoire heads into a pivotal presidential election, five candidates are competing amid calls for reform and reconciliation in a poll set against lingering political tensions. But only one is expected to win.

campaign

ACTING CJ

The Acting Chief Justice, His Lordship Justice Paul Baffoe-Bonnie, together with the entire Judiciary and the Judicial Service of Ghana, has extended heartfelt condolences to the family of the late Nana Konadu Agyemang Rawllings

campaign

COURT

The Human Rights Division of the High Court has adjourned to November 25, 2025, the case involving former Finance Minister Kenneth Ofori-Atta and the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP).

campaign

MISSILES

Zelenskyy is in the UK for a meeting of Ukraine's key European allies, the so-called "coalition of the willing. The trip comes after EU leaders vowed to keep funding Kyiv's defense.

campaign

CHINA TRIP

German Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul has postponed his planned visit to China after Beijing confirmed only one substantive meeting.

campaign

IVORY COAST

As Ivory Coast heads toward its presidential election, online disinformation is fueling unrest — spreading rumors about postponed mandates, voter fraud and political manipulation.

campaign

GHANA'S ILLICIT

In Ghana, gold is more than just a precious metal. From environmental destruction due to galamseys (illegal mines), to alleged funding of extremist violence through proceeds made from illegal mining, the country faces a complex crisis. DW’s Eddy Micah Jr. discusses this critical topic with extractives expert Solomon Kusi Ampofo, Maxwell Suuk, DW correspondent in Tamale and voices from the ground.

campaign

ITALIAN COURT

A court in Italy has given the go-ahead to extradite a Ukrainian suspect to Germany over the 2022 Nord Stream pipeline sabotage. The gas delivery route was long seen as a symbol of Germany's overreliance on Russian fuel.

campaign

CIVILIANS

Civilians in the Darfur city of el-Fasher are trapped and starving amid intense fighting, UN officials say. The paramilitary RSF says it has taken full control of what was the region's last major government-held city.

campaign

US-CHINA DEAL

US President Donald Trump has touched down in Tokyo, the next stop in his five day tour of Asia. Trump is scheduled to discuss regional economic and security issues with Japan's new prime minister on the visit.

campaign

HAPPIEST GERMANS

A new study finds life satisfaction in eastern Germany rising faster than in the west, although Hamburg is the happiest city. Meanwhile, Germany's domestic spy agency warns of rising espionage and sabotage.

campaign

ARSON ATTACK

Around 100 trips have been affected, including on the main line between Paris and Marseille. Repair work is set to last until early evening, with full operations not expected to be restored until Tuesday morning.

campaign

PROTESTERS

Police have fired teargas at supporters of opposition candidate Issa Tchiroma Bakary, who says he beat veteran leader Paul Biya in Cameroon's recent presidential elections.

campaign

FESTIVITIES

The Dutch capital is culminating celebrations for its 750th year of official existence. Events are taking place throughout the city, with the royal family also participating.

campaign

ILLEGAL GOLD MINING GROWS IN GHANA

Grassroots task force created to combat the mining that has poisoned rivers in one of the world’s largest gold producing countries.

campaign

MERCURY CONTAMINATION IN ATRATO RIVER

It’s home to predominantly Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities that rely on fishing and small-scale farming — livelihoods now imperiled by toxic pollution.

campaign

COCOA FARMERS TO PROTECT FORESTS

Farmers are learning to grow cocoa while restoring the very forests their livelihoods depend on.

campaign

HIGH IMPORT DUTIES, NOT FUEL PRICES

The duty remains very high, and it’s not making things easy,Mrs. Fianu emphasized and appealed to President John Dramani Mahama to fulfill his promise

campaign

A LOT OF PEOPLE DIDN’T LIKE THAT GENTLEMAN

Donald Trump said Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman “knew nothing about” the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi

campaign

IMF URGES GHANA TO CUT TAX

(IMF) has recommended that Ghana reduce costly and poorly targeted tax incentives to close the gap between potential and actual revenue collections

campaign

DEBATE OVER GHANA’S FOUR YEAR TERM LIMITS

Deputy Presidential Spokesperson Shamima Muslim, who described the current four year mandate as wholly insufficient for sustainable development.

campaign

SMUGGLING CANNABIS AT AIRPORT

The Narcotics Control Commission (NACOC) has arrested a South African national at Kotoka International Airport (KIA) for attempting to smuggle over 30 kilograms of cannabis into Ghana.

campaign

COMMUNITIES BLAME COMPANIES

Communities in mining areas continue to demand water, schools, clinics, roads and other basic amenities from mining companies

campaign

A .I. TRANSFORMS WATERMARKS

Artificial Intelligence (AI) powered watermark removal tools have revolutionized content creation across digital platforms

campaign

VEGETABLE PRICES SURGE

Ghanaians returning from city markets, have been struck by what feels like a silent food crisis, as vegetables become increasingly expensive.

campaign

MANHYIA PALACE AGREED ON THE DATE

The late Charles Kwadwo Fosu, popularly known as Daddy Lumba, passed away at age 60 on July 26, 2025

campaign

RALLIES FOR WORLD AIDS DAY, ICASA 2025

GHANET on Saturday led a massive 13–kilometer health walk to commemorate World AIDS Day 2025 and raise awareness

campaign

KEYS TO END GALAMSEY

Dr. Joyce Aryee has emphasized that ethical leadership is critical to winning Ghana’s battle against illegal mining, commonly known as galamsey

campaign

DADDY LUMBA’S LEGACY

Plans are underway to hold international funeral extensions in honour of the late highlife legend Daddy Lumba, his sister Faustina Fosu has revealed.

campaign

PAN AFRICAN AI SUMMIT RETURNS TO ACCRA

The Pan African AI Summit will return to Accra on September 22 and 23, 2026 at Kempinski Hotel Gold Coast City

campaign

VOLKSWAGEN INVESTS THREE BILLION EUROS

Volkswagen has invested €3 billion in a research and development center in Hefei, China, marking its largest investment outside Germany as the automaker fights to regain market

campaign

29 ENTREPRENEURS GRADUATED

Islamic Development Bank Institute (IsDBI) and Prince Mohammed Bin Salman College of Business and Entrepreneurship (MBSC) graduated 29 entrepreneurs from 20 member countries

campaign

CONTACT ANGLOGOLD ASHANTI

AngloGold Ashanti Executive Director Sells Over Three Million Dollars in Shares

campaign

FIVE WOUNDED IN ISRAELI STRIKES

Hamas says Israel’s ‘blatant, outrageous’ violations threaten deal.So Israel must fully and without delay withdraw from the Gaza Strip, as affirmed by this council.

campaign

MINING LAW EXPOSED 89 PERCENT

Environmental civil society organisations have revealed that the recently revoked Legislative Instrument (L.I.) 2462 exposed up to 89 percent of Ghana’s forest reserves to mining activities,

campaign

GHANA PARTNERS UNIVERSITY OF TOKYO

Ghana is seeking to accelerate artificial intelligence and data science skills development following high level talks between Communication Minister Samuel Nartey George

campaign

MONTH LONG FESTIVAL

Detty December 2025 delivers a packed calendar of concerts, beach parties and cultural celebrations

campaign

FRAUD CASE EXPOSES CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

What is emerging from the Wontumi Farms case is a broader conversation about how corporate governance works in practice in Ghana

campaign

MILITARY HARRASSMENT IN AFIENYA

Asafoatse Akroboso III of the Larkpleh family of Prampram in the Greater Accra Region has expressed worry over an alledged military harrassment over their properties at Afienya.

campaign

MP PLEADS WITH GOVERNMENT

The Member of Parliament for Amenfi Central, has made an urgent appeal to the government to prioritize the rehabilitation of several key roads in her constituency

campaign

MANY GHANAIANS WERE UNCERTAIN

The MFWA boss highlighted the severity of the economic downturn, particularly the sharp depreciation of the cedi, as a moment that underscored how fragile national stability had become.

campaign

(GBV ) CALLED FOR MORE CYBER SECURITY

The Programmes Manager, therefore, called on parents, especially fathers to ensure that boys learnt and got involved in unpaid care work at home

campaign

WORKERS OPPOSE PRIVATE SECTOR

The Public Utility Workers Union (PUWU) has strongly opposed government’s reported move to appoint a transaction advisor for the (ECG)

campaign

GHANA GOLDBOD LOSSES

Since the release of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) report on December 17, 2025 showing losses of approximately 214 million dollars from operations between January and September 2025

campaign

JOSHUA FAMILY UNABLE TO VISIT BOXER

The family of world heavyweight boxing champion Anthony Joshua has expressed deep concern following a fatal road crash on Monday that left two of his close associates dead and the boxer hospitalized.

campaign

TAKYI STOPS DOWUONA

Olympic bronze medalist Samuel Takyi delivered a dominant performance at the Idrowhyt Events Centre

forcing Isaac Dowuona to retire after just two rounds before issuing a challenge to national lightweight champion Joseph Commey.

campaign

GHANA PURSUES YEAR ROUND TOURISM

The Adinkra Group, headquartered in Washington, DC with operations in Ghana, has been instrumental in facilitating diaspora connections to the country.

campaign

COURT ADJOURNS NANA AGRADAA APPEAL

The Amasaman High Court has adjourned the appeal hearing of former fetish priestess turned evangelist, Patricia Asiedua Asiamah, popularly known as Nana Agradaa, to February 5,

campaign

GPRTU TASK FORCE ARRESTS 15 DRIVERS

(GPRTU) has arrested 15 drivers in Ablekuma, Accra, for allegedly charging multiple fares, the union’s task force has confirmed.

campaign

RAILWAY WARNS PUBLIC AGAINST FAKE SECURITY

(GRDA) has cautioned the public against collecting money on its behalf, insisting that it has not authorised the National Security Secretariat

campaign

NPP PRESIDENTIAL ASPIRANTS SIGN PEACE PACT

The MoU, undertaken in good faith and in the spirit of patriotism, loyalty, unity and party cohesion, commits the candidates to remain faithful, loyal and supportive

campaign

AREA RAZED BY FIRE

Fire razed dozen of shop in Ayawaso Central Municipal Assemble near Kwame Nkrumah Circle at Royal VVIP Station

campaign

AMA DEMOLISHES UNAUTHORISED STRUCTURES

The operation, led by the Mayor of Accra, Michael Kpakpo Allotey, covered areas including the Awudome Cemetery stretch, the Awudome roundabout,

campaign

GHANA'S COCOA FARMERS ARE UNPAID

The revamped system, introduced for the 2024/25 season, shifted the burden of pre-financing purchases from the Ghana Cocoa Board, or COCOBOD, to international traders.

campaign

SUPREME COURT OVERTURNS HIGH COURT

Supreme Court has, by a 4–1 majority, overturned the High Court's ruling annulling the Kpandai parliamentary election won by the New Patriotic Party (NPP)'s Matthew Nyindam

campaign

ACCELERATE ROAD CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS IN 2026,

The President had consistently emphasised the importance of modernising the country’s road network and had backed this with concrete budgetary allocations.

campaign

CENTRAL BANK CUTS POLICY RATE

Ghana's central bank cut its main interest rate (GHCBIR=ECI), opens new tab by 250 basis points to 15.50% in a decision announced on Wednesday, exceeding most economists' expectations.

campaign

STRONG GDP GROWTH IN 2026

Ghana's headline inflation is projected to align closely with the medium-term target, while economic growth is expected to remain strong in 2026

campaign

A CALLED FOR COORDINATED REFORMS

The forum formed part of activities marking the International Day of Education and the launch of the annual Educational Times Dialogue.

campaign

SCHOLARSHIP SCHEME FOR AFIGYA KWABRE SOUTH

Patricia Pearl Ankrah, has announced the assembly's plans to establish a scholarship scheme to support brilliant needy students within her district.

campaign

GHANA OFFERS LEVY CUT

Ghana's finance minister has offered to cut a mining levy by two percentage points to help push through a new gold royalty regime

campaign

SCHOOL FEEDING PROGRAMME INSPECTS SCHOOLS

The exercise, conducted between January 26 and 30, 2026, formed part of the programme’s routine quality assurance measures aimed at improving service delivery under the national school feeding policy

campaign

ETHIOPIA DEMANDS ERITREA TO WITHDRAW’ TROOPS

The two longstanding foes had waged war against each other between 1998 and 2000, but signed a peace deal in 2018

campaign

THE GOVERNMENT AND THE CHRISTIAN COUNCIL

Highlighting the significance of Ghana’s youthful population, the minister noted that individuals aged 15 to 35 constitute about 38 per cent of the population

campaign

ECONOMIC GROWTH SLOWS TO 4.2%

GHANA’S economic growth slowed by 4.2 per cent in November 2025 as compared with 7.1 per cent in the same period in 2024, the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) has revealed.

campaign

GOVT UNVEILS COCOA SECTOR REFORMS

The new producer price, effective Thursday, February 12, 2026, is GH¢41,392 per tonne (GH¢2,587 per bag), representing 90 per cent of the gross FOB price of $4,200 per tonne.

campaign

GOVT MOVES TO AMEND CHIEFTAINCY ACT

The Government has begun processes to amend the Chieftaincy Act, 2008 (Act 759), to enhance the effectiveness of the institution of chieftaincy within Ghana’s governance framework.

campaign

CHARGED WITH USING MILITARY ACCOUTREMENT

A 34-year-old Joseph Baadah admitted he was not a soldier and told the court he wore the uniform to impress a nurse he had fallen in love with